Many intelligence agencies were caught off-guard by the Arab Spring in 2011. Similarly, many agencies failed to anticipate the Islamic State taking over Mosul in 2014. Yet, the reasons behind these instances of strategic surprise were not new at all. They were already apparent over 25 years before, prior to the Iranian Revolution, and still pervade contemporary intelligence work.

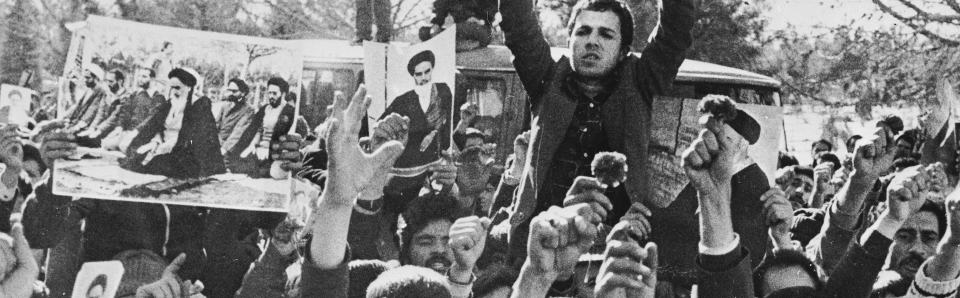

In the months leading up to Iran’s 1979 revolution, foreign intelligence communities failed to grasp the possibility that a Shi’ite cleric would topple an experienced monarchy with petrodollars to spend, a brutal coercive apparatus at home, and powerful allies abroad. As late as August 1978, the CIA assessed that ‘Iran [was] not in a revolutionary or even “prerevolutionary” situation’. A Defense Intelligence Agency report the following month even suggested the Shah was likely ‘to remain actively in power over the next ten years’. Until early November 1978, when the US ambassador to Tehran realised and reported on the popular anger against the Shah and support for Ayatollah Khomeini, these views still remained widespread.

There are many explanations for this intelligence failure. Despite Iran’s strategic importance to the United States – it was one of the United States’ two pillars of stability in the Persian Gulf alongside Saudi Arabia during the Nixon administration – Washington knew little about the country. Round two of the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT II), the Israeli-Egyptian peace talks, and the thawing of relations with communist China dominated intelligence priorities. Within Iran, the United States was not concerned with its domestic politics; it focused instead on maintaining its Tacksman sites in northern Iran, which monitored and intercepted telemetry signals from the Soviet Union’s development of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles across the border.

Problems of organisational structure in American intelligence also contributed to this strategic surprise. The CIA’s National Foreign Assessment Center only had four full-time Iran hands, with little interaction between desks, let alone with other agencies. Iran specialists did not even exist in other agencies, such as the DIA and the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research. Though the Tehran embassy had Iran experts, it was understaffed. Even the incoming US ambassador, William Sullivan, admitted knowing little about Iran and the Middle East. US intelligence assets in Iran had little contact with regular Iranians, let alone opposition members, thus limiting their interactions to the Shah’s court. Furthermore, embassy reports coming out of the country, already classified as a second-tier priority, focused on current rather than long-term strategic intelligence.

A failure of imagination was pervasive within the intelligence community; analysts did not consider scenarios that lacked precedent, nor did they seek out ‘dogs that don’t bark’. This problem was compounded by the tendency towards single-outcome forecasts, which excluded ‘black swan’ events. Meanwhile, the Shah gave the impression that things were under control. The opposition itself also appeared too fragmented to arouse concerns. Few expected revolutionaries to assume the form of religious reactionaries. Given the drawn-out pace of events, analysts tended to discount incremental developments.

The intelligence failure was compounded at the policymaking level. Disagreements flared over the significance of developments inside Iran. US President Jimmy Carter’s national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, viewed Iran’s political tumult through a Cold War lens, and supported the Shah using brute force to crack down on the burgeoning unrest. This stance placed him at odds with other key figures, such as the Secretary of State, Cyrus Vance; the Director of Central Intelligence, Stansfield Turner; and the US ambassador to Iran, William Sullivan. Washington’s nearly unimpeachable confidence in the Shah’s ability and longevity also coloured policymakers’ views. The Carter administration wanted to preserve a valuable Middle Eastern ally, and the structure of the US intelligence community made it hard for alternative views to rise to the policymaking level.

Decades after the fall of the Shah and the 1979 revolution, the United States faced another high-profile intelligence failure in the run-up to the Iraq War. In the Bush administration-sponsored 2005 Iraq Intelligence Commission, the authors traced Iraq’s WMD fiasco to defects in information-sharing protocols and mechanisms among agencies, ‘excessive adherence to conventional thinking’, and the ‘timidity…in challenging the orthodoxies of…superiors’. The report showed how little had changed since Iran. Resistance to change and reform in intelligence organisations is everywhere, and the United States is hardly immune to the problem.

This article by Open Briefing senior analyst Kevjn Lim was first published by the Yale Journal of International Affairs on 8 November 2016.